I visited an architecture firm for the first time in 2007–a small residential office tucked into an historic brick building on Loring Park. The conference room was in a decommissioned freight elevator and the walls were covered with drawings of houses. It was all unbelievably cool. The architect who showed me around stopped at a monitor hooked up to a massive PC running software from the movie industry. They used it to create computer-generated images—or renderings. This time-consuming and processing-heavy task was not, back then, adopted widely by residential architects, especially not small firms like the one I was visiting. I’d never seen anything like it before. It was like magic—a highly-pixelated image very slowly (sometimes taking longer than 24 hours) coming into focus to reveal the building that was being designed.

In the fifteen years since that visit, computers have become vastly more powerful and renderings have become ubiquitous in architectural design.

SALA partner Jody McGuire recently shared a conversation she had with a prominent New York architect, including his thoughts about renderings, which were, basically, “don’t do them.” Instead, his firm builds physical models of all their projects.

I’m not sure why he has taken this approach, but I can imagine several advantages. Renderings produced by architects are often too realistic, too detailed, and simultaneously not realistic or detailed enough. If there is an appropriate time to attempt this type of photorealism, I believe it is when the design-thinking has begun to settle and the scheme has concretized. Before that time, renderings can often suggest things that we don’t intend, and force designers to assign surrogate materials to every element, even if those assignments are not carefully considered. Renderings open the door wide to misrepresentation, and slam the door shut to other opportunities. Renderings can unintentionally convince a viewer that the design is finished. After all, renderings often look like polished buildings inhabited by people and cars and often a flock of birds overhead.

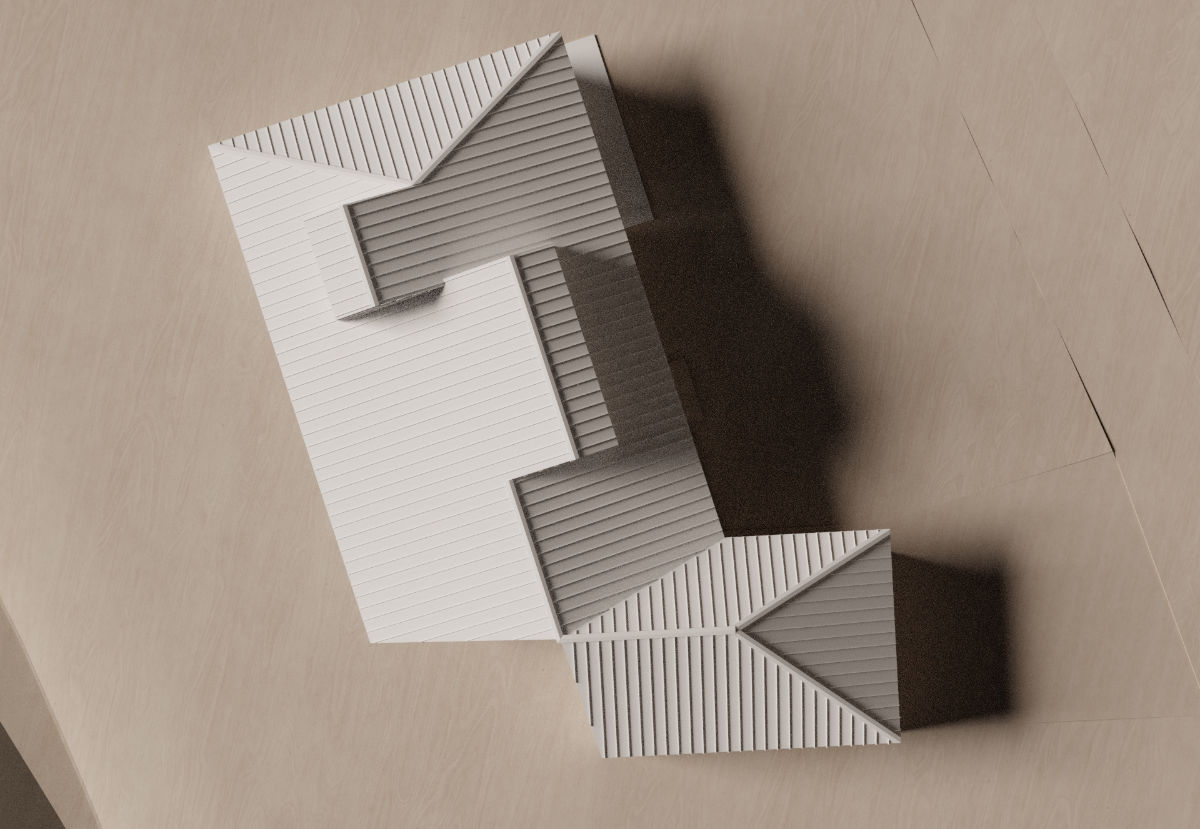

I also prefer physical models. I love the way models give the viewer an opportunity to imagine the vast, un-tapped potential of the design process. A model made of cardboard is easily understood as an analog for something else—it’s built at a scale too tiny to show every condition perfectly resolved. This allows for open-ended imagination. Many possibilities can coexist, even though the model sits before you as a finished object.

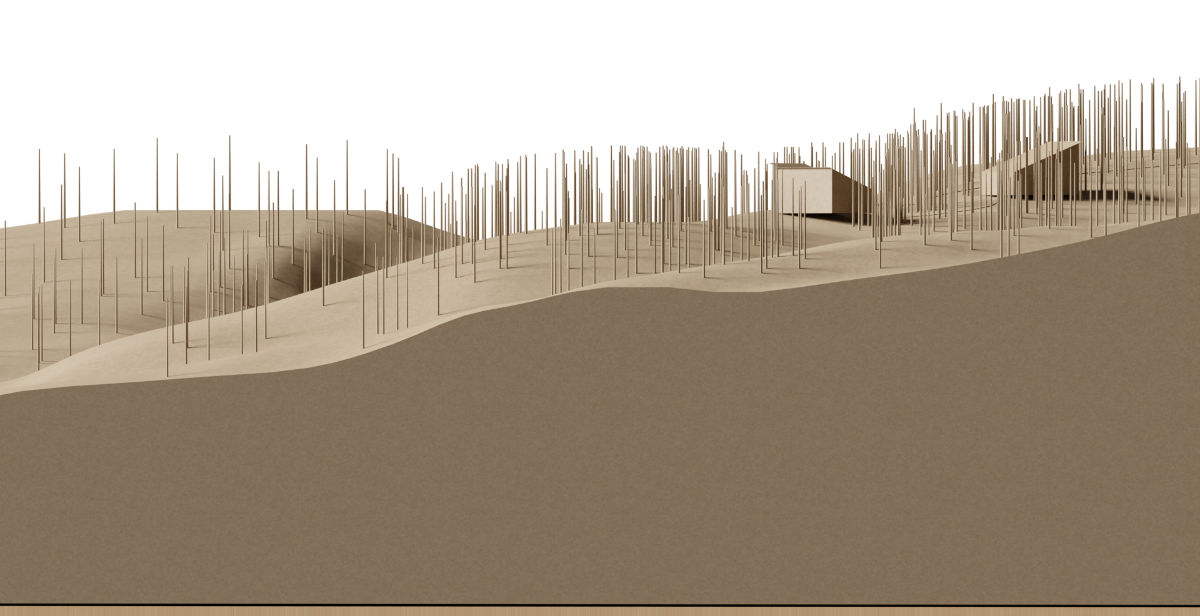

In grad school, I spent a semester working with Seth Thompson (adjunct assistant professor at Columbia University and founder of the design studio A Lot of Moving Parts) constructing an enormous collection of computer models. We then rendered the models to appear as though they were physical scale models. The models collectively became the set and the subjects of an animated short film that we produced. We used this approach for two reasons. First, we wanted our project to be playful and approachable; we strove for something beguiling and whimsical to suggest that the design work wasn’t finished, leaving room for the casual observer to project their own ideas onto what we had done. Second, we had nowhere near enough time or resources to actually build the sets and film them.

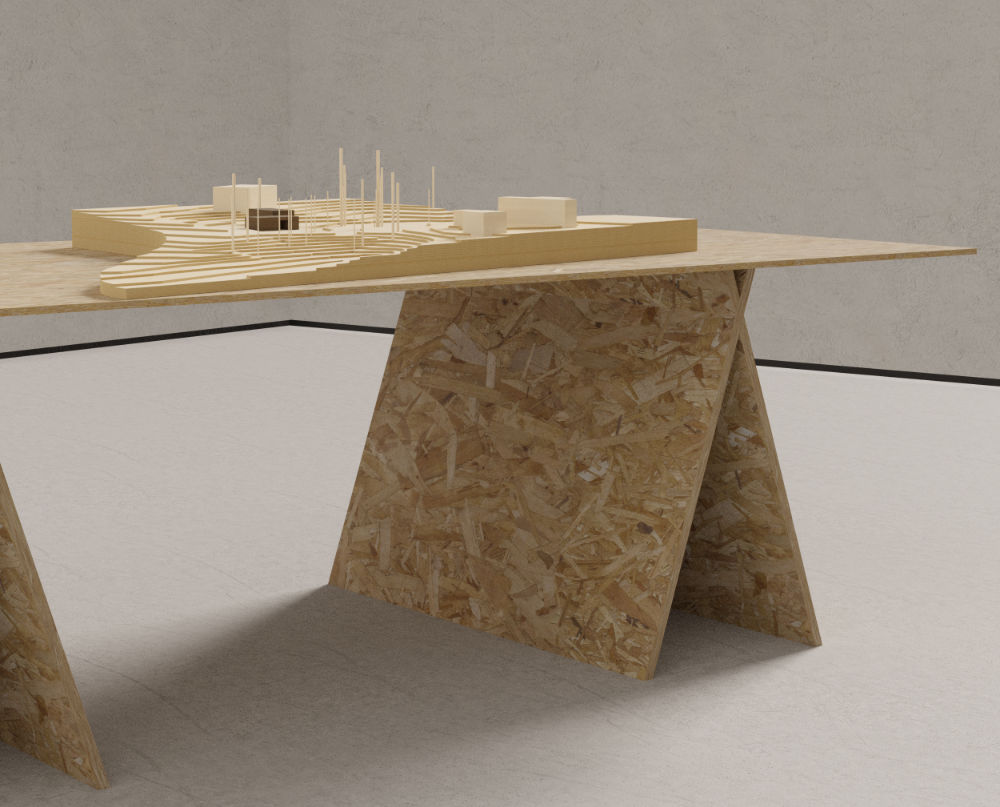

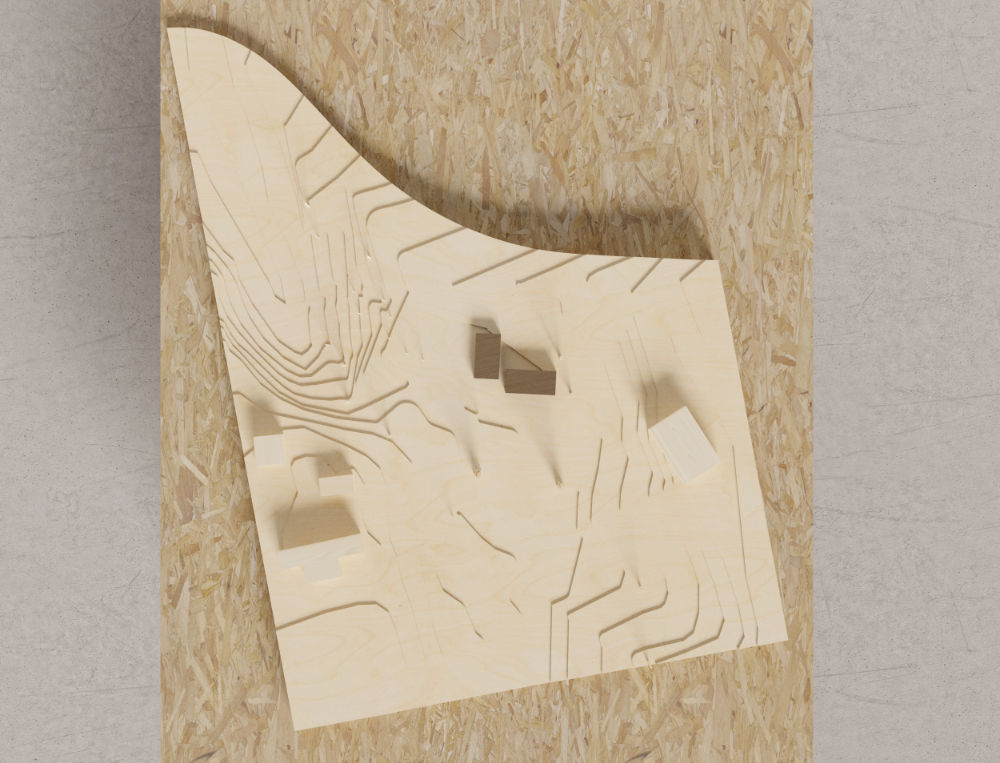

I’ve remained interested in rendering digital models to appear as though they are hand-made physical models. Since finishing school and joining SALA, I’ve continued to use this digital/physical style to make what appear to be well-crafted architectural models in a matter of minutes rather than the days it would take to carefully build them from basswood and chipboard with an x-acto blade and straight-edge. I’m not advocating for the elimination of photorealistic renderings (a few examples appear in this blog), but instead for a careful look at how these tools can be used in fun, productive, and surprising ways in architectural design.