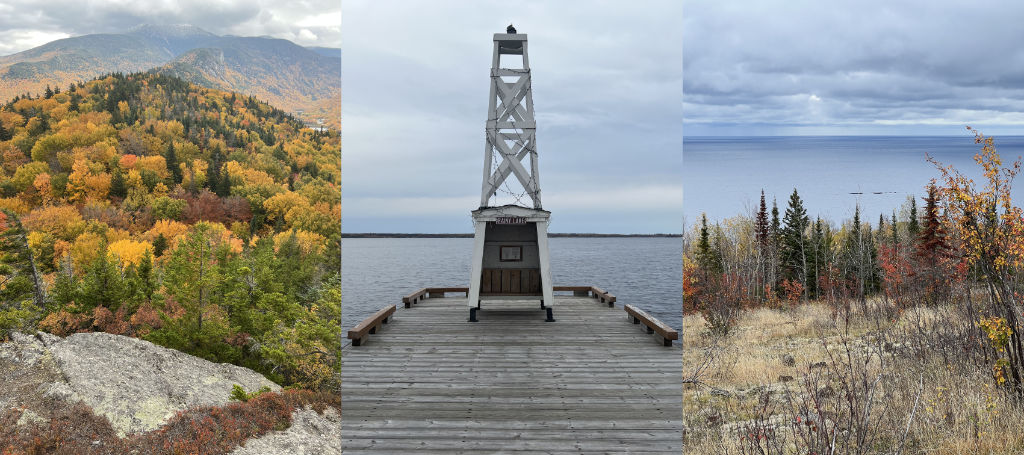

I was extremely fortunate to have the opportunity to travel to three varied and distinct destinations for potential projects in the month of October, from the northern boundaries of Minnesota to the eastern regions of Vermont, and all in the crisp beauty of fall. Each potential project is a common type for us—a single-family home or retreat—but each design will ultimately be influenced in unique ways by its location.

I was extremely fortunate to have the opportunity to travel to three varied and distinct destinations for potential projects in the month of October, from the northern boundaries of Minnesota to the eastern regions of Vermont, and all in the crisp beauty of fall. Each potential project is a common type for us—a single-family home or retreat—but each design will ultimately be influenced in unique ways by its location.

So what does an architect consider during an initial site visit?

First, and foremost, is the opportunity to discuss goals of each project with its owner on location, or in situ. Two of the three clients I was meeting for the first time, so these visits were as much about building a personal relationship as gaining a deeper understanding of the project site.

Second, is walking the property and getting a feel for a place—its views, contours, ground cover and vegetation, etc. The sites I’m referring to were significantly varied and included a lakeside city lot in International Falls, MN, damaged in last spring’s flood; a ledge rock hillside overlooking Lake Superior near Grand Marais, MN; and rural, forested acreage in East-central Vermont with previously logged building sites.

Second, is walking the property and getting a feel for a place—its views, contours, ground cover and vegetation, etc. The sites I’m referring to were significantly varied and included a lakeside city lot in International Falls, MN, damaged in last spring’s flood; a ledge rock hillside overlooking Lake Superior near Grand Marais, MN; and rural, forested acreage in East-central Vermont with previously logged building sites.

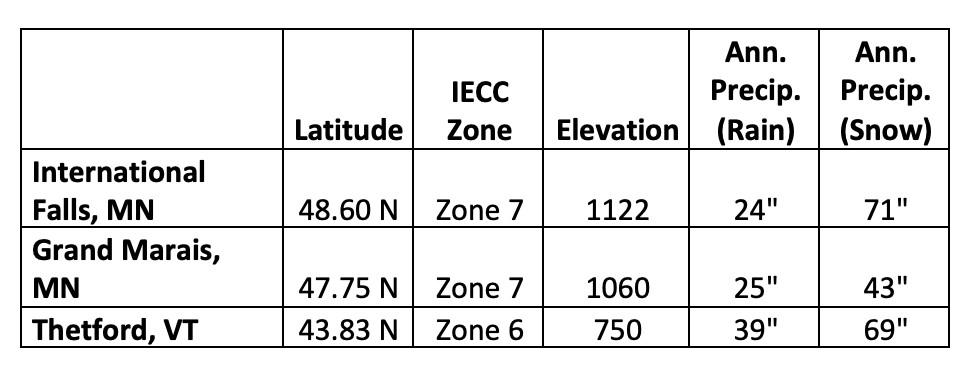

Third, is reviewing available data. The following chart is only a small sample of what is available and compiled by me for comparison. I’ve included latitude, IECC climate zones, elevation (above sea level) and annual precipitation, because they will be useful data points—at least for these projects—to consider for successful, and localized, designs. These data points are related to, but independent of, local zoning regulations and building codes that will also guide each project.

One of the most revealing benefits of this comparison was in uncovering incorrect assumptions. In the rolling and mountainous winter ski haven of Vermont, I found myself lower in elevation, latitude and climate zone requirements than my prospects in Northern Minnesota!

One of the most revealing benefits of this comparison was in uncovering incorrect assumptions. In the rolling and mountainous winter ski haven of Vermont, I found myself lower in elevation, latitude and climate zone requirements than my prospects in Northern Minnesota!

So how do architects design with this information?

Let’s look at what latitude reveals first. Any location on the planet exists at a specific latitude (horizontal axis) and longitude (vertical axis). Specific locations on each axis can be used to pinpoint a specific location (coordinates) anywhere on the planet—just ask your phone! As the earth predictably spins on its axis while rotating around the sun, successful design considerations can be predicted, too.

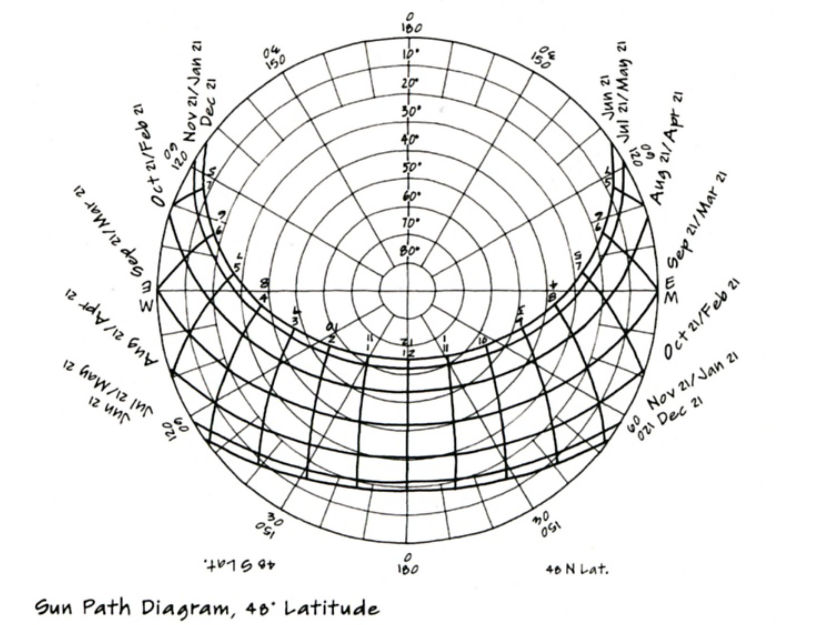

Below is a Solar Path diagram example for 48º North, which includes International Falls. To understand this chart, think of it as a domed compass with North being at the top. Each radial circle represents a 10 degree increase from the horizontal plane to 90 degrees vertical at the center. Now imagine your building site in the center of this circle. The curved lines that arc from side to side represent the sun’s path, rising in the East and setting in the West. At noon (Standard Time), the sun is at its highest point in the sky (and center of the chart), and that angle (the sun’s Altitude) is highest in June and lowest in December.

What’s important about this chart for designers is that it allows us to reliably predict the movement of the sun around any site and use it to design features such as overhangs for solar control and openings for daylight. This chart allows you to predict where the sun will fall within a design at any time of the day and year, even without asking your phone.

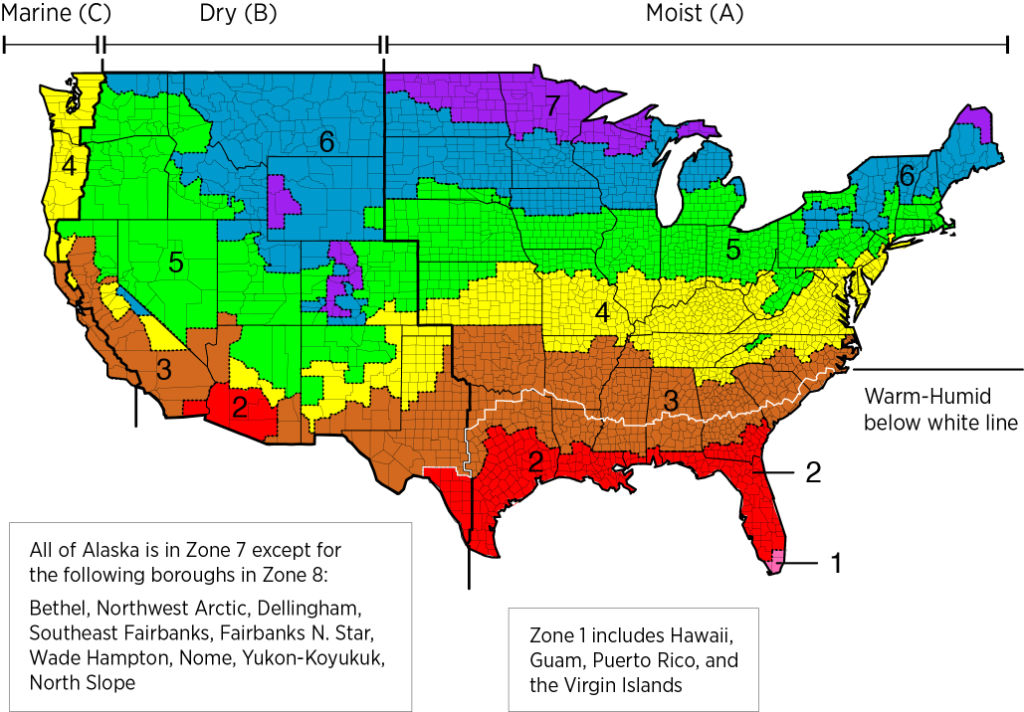

Next is the International Energy Conservation Code Zone which assigns a value of 1 (very hot) through 8 (extremely cold) across a map of the United States. These values are used by building codes and building scientists to assign and recommend minimum requirements for insulation, air-sealing, and glazing. All of the sites I’ve mentioned are considered “cold climates”—no surprise, I’m sure—so the recommendations between Zones 6 and 7 will vary minimally.

The next data point on the chart is elevation above sea level. For these projects, elevations are relatively close and not particularly project-critical, except that last year Rainy Lake saw its wettest year on record. That, on top of a late spring thaw, resulted in a record setting lake elevation of 1113.2 that caused devastating flooding and exhausting protective measures for many on the south shore of the lake, making design elevations for a new structure critical to long term project durability and safety.

Last on the chart, but certainly not of possible considerations, is annual precipitation. As mentioned above, Rainy Lake saw exceptional precipitation creating a unique event, but precipitation averages remain useful for other considerations. They may inform a design’s roof shape, structural requirements, wall assemblies, etc. For example, because the Vermont project will be subject to about 56% more annual rainfall (on average) than either project in Minnesota, the wall design may need to be designed for greater drying potential, whereas the structural requirements of the roof to support snow loads will be very similar between Vermont and the International Falls project. (Note: many of these factors are also prescribed by State or local building codes, but understanding the basis for those codes is helpful in designing for their intentions.)

Last on the chart, but certainly not of possible considerations, is annual precipitation. As mentioned above, Rainy Lake saw exceptional precipitation creating a unique event, but precipitation averages remain useful for other considerations. They may inform a design’s roof shape, structural requirements, wall assemblies, etc. For example, because the Vermont project will be subject to about 56% more annual rainfall (on average) than either project in Minnesota, the wall design may need to be designed for greater drying potential, whereas the structural requirements of the roof to support snow loads will be very similar between Vermont and the International Falls project. (Note: many of these factors are also prescribed by State or local building codes, but understanding the basis for those codes is helpful in designing for their intentions.)

It’s difficult to put a value on these visits. They are so much more than the site. They’re memory making—meeting families, enjoying lunch, toasting cocktails, side-stepping Cladonia rangiferina (aka Reindeer Moss)—and relationship building. They build a communal investment in the success of each project and they are a joy. Though it’s unlikely I’ll hit peak fall color in Vermont again, I look forward to my next opportunity to visit any of these places, and people.