A few years ago, a contractor asked if I would help he and his wife design a new home for themselves. The contractor and I had worked together early in my career on a project that would prove seminal to their request. I was somewhat conflicted about the proposition because the delivery posited that the design work would be limited.

I mean no disrespect when I say architects hear versions of this a lot. I only need a plan; I already know what I want; I just need a little design. The message rarely reveals the cause, which is typically a fear of unknown cost or a simple lack of design knowledge and experience. This is not the fault of the messenger. Our disposable product-based culture does a terrible disservice exemplifying the true value of creative endeavors and durable goods. But I digress.

In hindsight, I had misread the “limited” nature of the work I was being asked to do. What this couple was really asking for was design work. What they were uniquely able to limit was the amount of technical documentation required to bring the design to life through construction. Below are a few highlights from our collaboration.

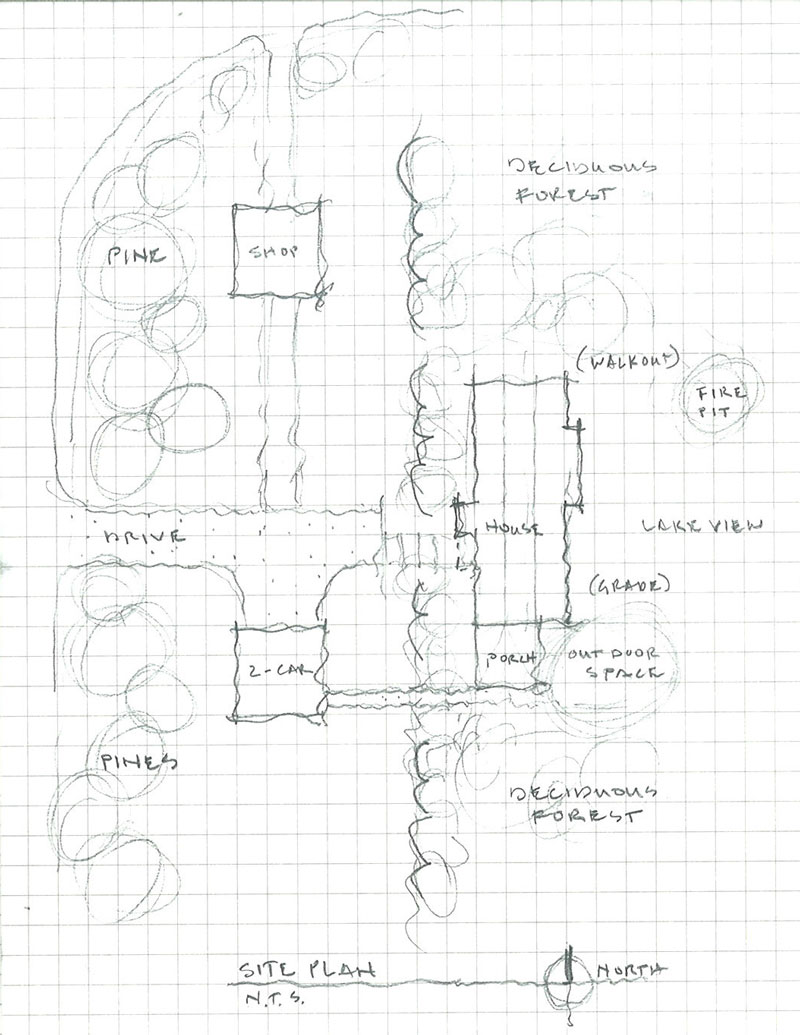

Our first visit started like any other, with a walking tour of the property. A previously assumed location for the new house proved inferior to the one ultimately settled on by our walking and talking. This flatter, more open plateau would require fewer trees to be removed and provide a more stable building site, still with walkout access.

My initial sketch for the site detached the garage from the house, placing it opposite a future pole shed for construction storage. The intention was to reduce the overall scale of the house and garage. (When you consider the width and depth of a new three-, or even two-car garage, it often exceeds the overall width of many of our homes, which are kept narrow to provide daylight throughout.) Unfortunately for me—who admittedly didn’t have to live in this rural, northern site and shovel a regular path between three buildings—my argument was understandably lost. The first scheme was revised with the garage attached, but the owners remained sensitive to my garage-to-house ratio argument.

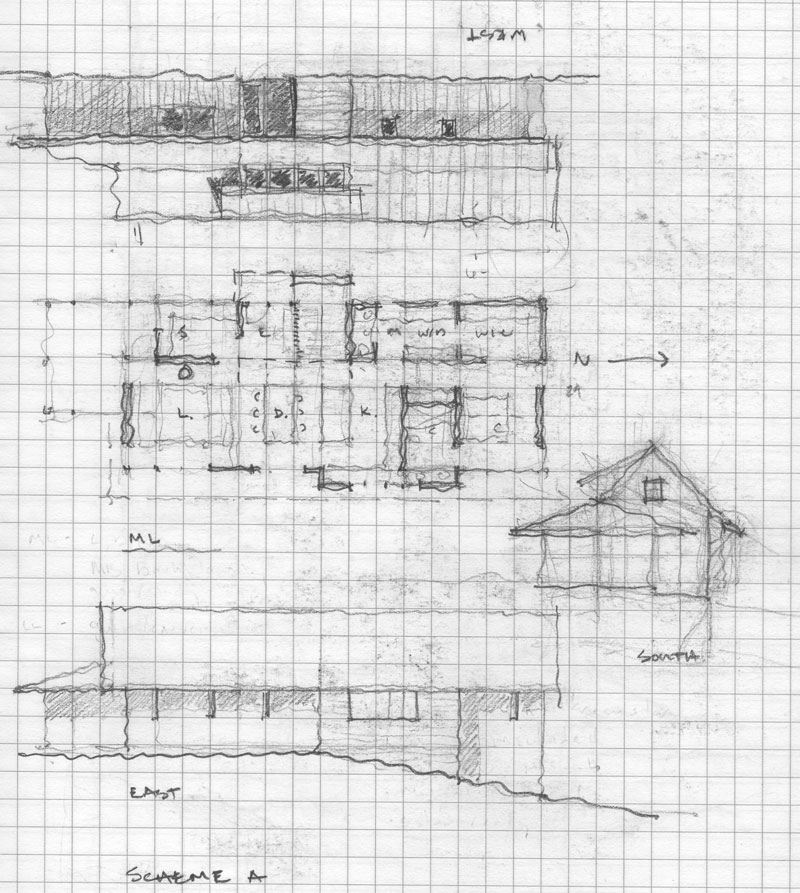

Our conversation and exploration resulted in a two-pitch roof design, familiar in the rural agricultural vernacular of lean-to sheds and farmsteads expanded over time. This kept the primary gabled ridge of the house above that of the low-slung garage and porch roofs, prompting the owners to nickname the house Isanti Shanty!

While considering the roof massing options we were simultaneously exploring design opportunities within the framing structure. Incidentally, the owner is a framer at heart, and employs a framing crew in practice. To maximize the value of experience we explored repetitive framing variations that would create dynamic visual interest and daylight throughout the living space.

Our first effort highlighted an exposed timber or truss frame. Confession: I’m still a little enamored with this one, but ultimately the increased attention to detail and material quality required to expose framing drove this scheme beyond the budget goal. Not to mention the potential for wildlife to gather in the exposed outer rafters! Ultimately, the solution rested on a more common enclosed scissor truss profile running from end to end, broken only at a unique reverse-shed dormer.

Early in the process, the owners had expressed their desire for a Mid-Century bent to the home’s interior. As the structural form of the home began to reference the rural vernacular, I began to struggle with the potential discord between interior and exterior and was open about my concern. Thankfully, the emergence of the unconventional reverse-shed dormer created a language to combine the familiar exterior gabled form with some playful Mid-Century details inside, including the large clerestory, walnut room dividers and a sunken living room.

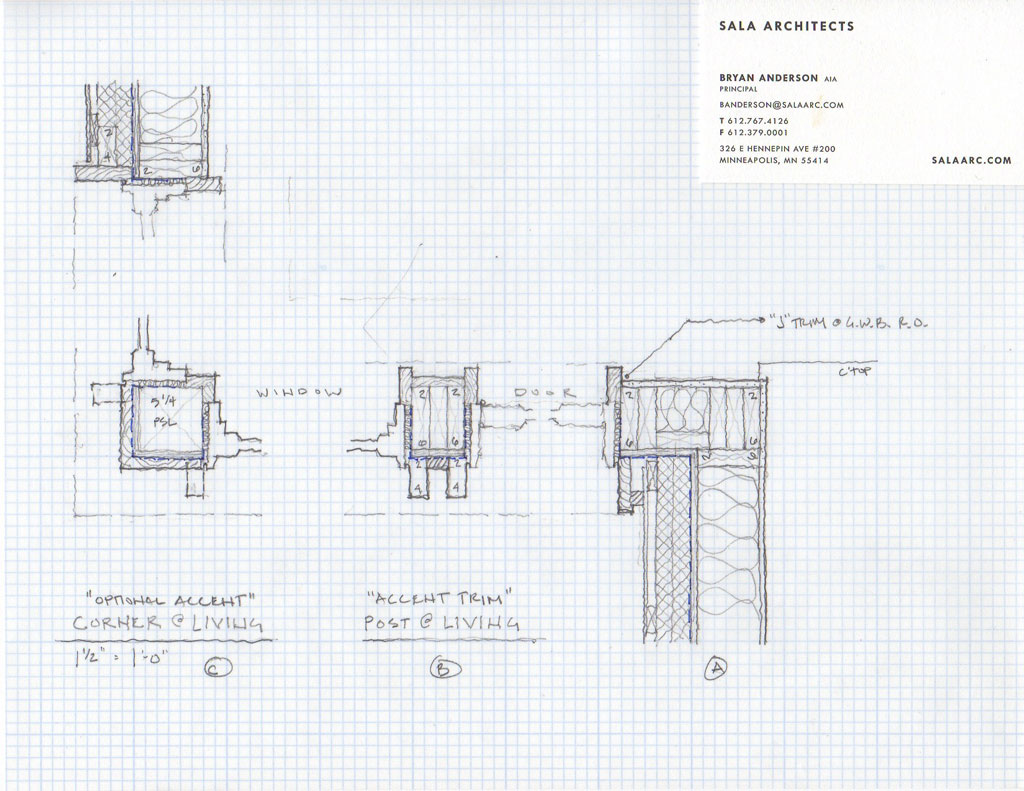

Even in a project with limited scope, the design solution doesn’t stop at plan and form. Material selection, construction assembly, and energy efficiency are all best considered early in the process. Finding a progressive “best practice” is often a stumbling block when the book-learned architect faces off against the empirically knowledgeable contractor. In this case, the contractor-as-owner was personally motivated to expand his knowledge of continuous exterior insulation—a system proven to elevate energy efficiency but unfamiliar to, or even resisted by, many homebuilders. Here the detailing was especially rewarding because we both brought ideas and materials to the table in energetic dialogue rather than a focus on risk and liability.

Similarly, the owners took the lead on many products and finishes, consulting with me when needed, and sometimes just for fun! Because we had developed the language of the house together—meaning the elements that defined the design—through dialogue, sketching, and computer models, the owners understood what they were going to build.

As thorough as this design process may sound, it really was just the beginning. For most clients, this initial, yet very complex exploration of alternatives and solutions, still needs to be exhaustively documented to ensure that the chosen contractor understands the solution in order to accurately price and build the design. It was only because owner and builder were one in the same, and took on the responsibilities of documentation, that the project could successfully leap from design solution to construction. Architecture, abridged.