It’s been exactly one year since I joined SALA. Markers of time—including workversaries like this one—prompt us to consider just how quickly that great river is flowing. For me, such consideration often leads to reflections not only on where I am going, but where I’ve been. That’s in part why I’ve been thinking about the pandemic summer of 2020, which I spent with a small team of friends designing and building a small research station off the coast of Connecticut in the Long Island Sound, on Horse Island, the largest of the Thimble Islands.

The idea for the station began in 2019 with a dream shared by Dave Skelly, director of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, and Alan Organschi, partner at Gray Organschi Architecture and director of the Regenerative Building Lab at the Yale School of Architecture.

The two organized a seminar to research Horse Island, owned by Yale and operated by the Peabody Museum. Still a student at Yale, I participated in that seminar, where my classmates and I focused on the challenge of locating a small, off-grid research station somewhere on the island while carefully adhering to principles of regenerative design. Our research scope included areas of local supply chains, ecology, energy production and water collection, design for disassembly and prefabrication and other relevant topics. As the seminar concluded—our final months were spent on Zoom due to lockdowns—we provided our findings to a team of ten design-build fellows including myself. The fellowship afforded us the opportunity to spend the next six months applying the research to design and construct the building. For more on the background of the project, check out this article in Metropolis Magazine.

The 2-month design process, which we also conducted remotely due to the pandemic, was intense and collaborative and all-consuming. By the end of July I had memorized every piece of the detailed digital model we used to produce the construction drawings. After almost five months collaborating only virtually, it felt unbelievably refreshing to hop on a ferry and finally begin work on the island.

Our early field work involved selectively clearing trees and preparing the site for construction. Meanwhile, at a warehouse on Yale’s west campus, we began to pre-fabricate and test-fit the building structure and components.

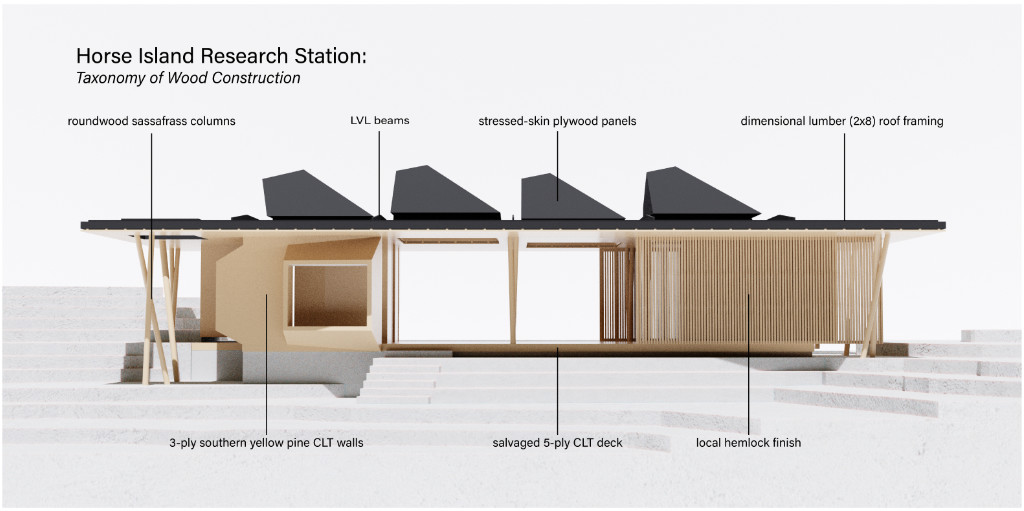

Nearly every part of the building is made from wood: repurposed 5-ply cross-laminated timber (CLT) floor panels span 16’ and work as carbon dioxide sinks (check out Timber City), 18” deep tapered laminated veneer lumber (LVL) beams spanning between roundwood sassafras columns (harvested on the island) carry the low-slope planted roof, which itself is framed with 2×8 doug fir.

Southern yellow pine CLT walls enclose the kitchen, bunks, and storage areas. Stressed-skin plywood panels form each face of the massive “barnacles” that serve as skylights, vents, and direct solar panels to the sun. The ceiling and the massive sliding doors are constructed from local hemlock grown at the nearby Yale-Myers forest. Each type of wood (engineered or solid) and its species and source were carefully selected based on the wood’s role within the structure. Once we finished each component, we sent it off to the island by barge.

We spent our days working tirelessly against a challenging schedule. We ate lunch outside sitting on CLT drops. Evenings and weekends, many of us sailed on the Java Jive, with captain Nick, a mechanical engineer and the design-build fellow responsible for the solar and rainwater collection systems.

I went swimming and played cards at Katie and Christine’s beach cabin. Our whole team camped out on the island and sat by the water’s edge mesmerized by the way the rising tide slowly swallowed our crackling bonfire.

During this time, our only reminder of the pandemic and its anxiety came in the form of sweaty facemasks plastered to our cheeks as we churned out stacks of roof joists in a stuffy warehouse in the heat of August.

It was easy to forget about the great challenges faced by our world during this time, even as we constructed a building that was intended to serve as an example for addressing the relationship between construction and our changing climate.

And as we fell into the rhythm of building and relaxing and the encompassing joy of both, time did that funny thing time does, and the number of days remaining shrank to a number smaller than the number of days that had passed.

Soon we traded tee shirts and high vis vests for thick yellow hoodies. The air turned chilly and cold crept through the uninsulated walls of the beach cabin where we ate dinner and played cards.

It became clear that we wouldn’t finish construction before I departed for Minneapolis, where my new job with SALA awaited. The bitter taste of leaving a place and a project I loved was tempered with the rush and excitement of starting something new. I followed my heart to Yale and to Horse Island and ultimately back to Minneapolis, my home.

I’m excited to continue thinking about the issues that the Horse Island research station seeks to address. And I look forward to returning to that rocky island, sliding open the heavy hemlock doors (just like this…), and looking up through those big barnacle skylights. I’m certain I’ll have a moment similar to this one, where I reflect on the wonderment and joy that summer brought me.