The long pine needles glisten with hoarfrost in the early light of this winter morning. Walking through foot-deep snow, I come to the edge of a pine grove and pass from open clearing to the shelter of the grove’s understory. It’s here, among the Pine Collection at the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum, that I find myself captivated by a transformation nearly three years in the making.

Back in January of 2007, I made the same snowy trek with temperatures hovering just above zero, to view potential building sites for the Arboretum’s annual summer sculpture exhibit. I was intent on submitting a design for their exhibit, themed enigmatically “Human/Nature”. I pondered what this might mean as a group of 40 of us –artists, architects, and landscape designers– stepped out the doors of the visitor center on a tour through the Arboretum’s grounds looking for possible inspiration.

As we trudged along a path that skirted a pine grove, I was struck by what I saw. Underneath and in between the tall evergreens, a mix of dark grey trunks, peeling crimson bark, and rich green boughs called to me. While the group moved on, I stopped in my tracks, secretly hoping no one else was noticing the magnetic pull I felt. This place begged me to step off the path and into its mysterious realm. I hastily snapped a few photographs, and caught back up to the group, but inside my head I was already scheming to create a design to inhabit this powerful space.

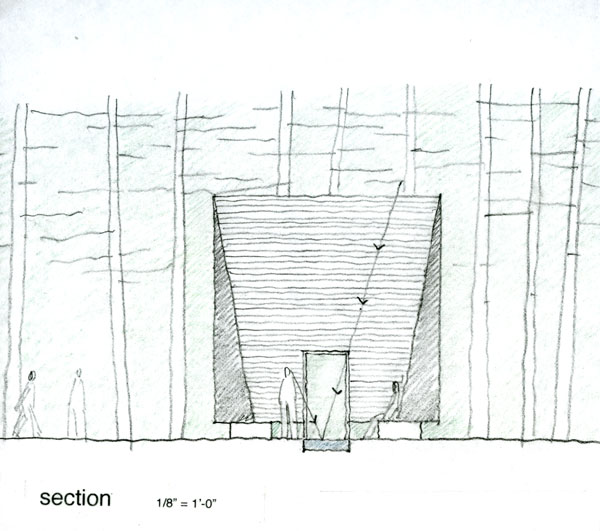

Back at SALA’s design studio in Minneapolis, I sketched out my idea: a wooden box that would provide a strong geometric contrast to the natural complexity of the tree trunks and canopy, and that would reveal a contemplative and meditative space within its walls. The form would take on the nature of Midwest corn-cribs –simple agrarian structures with spaced-slat siding used for drying corn– and would be open to the sky above. Sloped walls on the interior would focus attention upward, and allow visitors to lean back against the walls to a view through the pine boughs.

To my delight, PINE/Cone, as it was dubbed by a co-worker, was selected to be one of fifteen exhibits for that summer’s event. As I worked to create the detailed drawings and specifications for construction, certain elements fell neatly into place –the frame would be formed from sustainably harvested lumber, and the stone reflecting pool would be honed from local Mesabi Range granite. The choice of wood for the slats was a critical question to answer. It needed to be a durable wood, naturally decay resistant, and capable of standing up to Minnesota’s harsh climate. In addition, I wanted to avoid preservative treatments containing harmful toxins and volatile organic compounds. While western red cedar would have been a logical choice, I was concerned about transporting this material from half a continent away. Instead I was able to turn to Rajala Timber near Grand Rapids, MN, who sustainably harvest native tamarack.

Also known as larch, tamarack is a tree that grows across much of upper North America. While this softwood looks much like other conifers, with straight trunks and green pine needles, as the latin name Larix Decidua suggests, in the autumn it will lose it’s needles like deciduous trees lose their leaves. While the trees never grow very large, their golden fall color makes them one of the most striking trees in our state. It’s also a tree that grows readily in wet, swampy soil, and has thus evolved to be very resistant to rot and decay, making it exceptionally well-suited to outdoor use. Along with the fact that it’s grown and harvested in Minnesota, it made the perfect choice for cladding PINE/Cone.

PINE/Cone was never supposed to make it beyond October that year. But visitors along with staff at the Arboretum had become attached to this box in the woods, and there was a grassroots effort to extend the life of PINE/Cone. I was asked by the Arboretum if it would be okay to leave Pine/cone up indefinitely.

Every so often I make it back out to the Arboretum and visit Pine/Cone. On one particular visit several years after it was first installed, a thick ice fog hovered over the rolling hillsides of the arboretum depositing thick layers of rime on tree branches and needles. Passing into the grove, PINE/Cone came into view. For a moment, I felt as if I were looking at a black and white photo, for the tamarack cladding had all turned grey, and with the white snow and frosted pine needles, everything appeared without color –varied tones of grey, white and black.

Time has marked itself across the face of PINE/Cone. What once were gleaming, fresh-cut boards are now silvered, and grey. The tamarack boards have taken on a life and an aging that reveals the oxidizing effect of ultra-violet sunrays, of the battering of rain and snow, the repeated wetting and drying of the wood.

In today’s world of increased focus on “maintenance free” building materials, we lose something in the mystery and power that comes with materials that have been matured by the weathering of time, worn smooth by hundreds of hands passing over their surfaces, or in the stain of water that has tracked across their facade. Product manufacturers would have us believe that materials shouldn’t age, that surfaces ought always to look brand new –forever in a state as if their packaging was just removed.

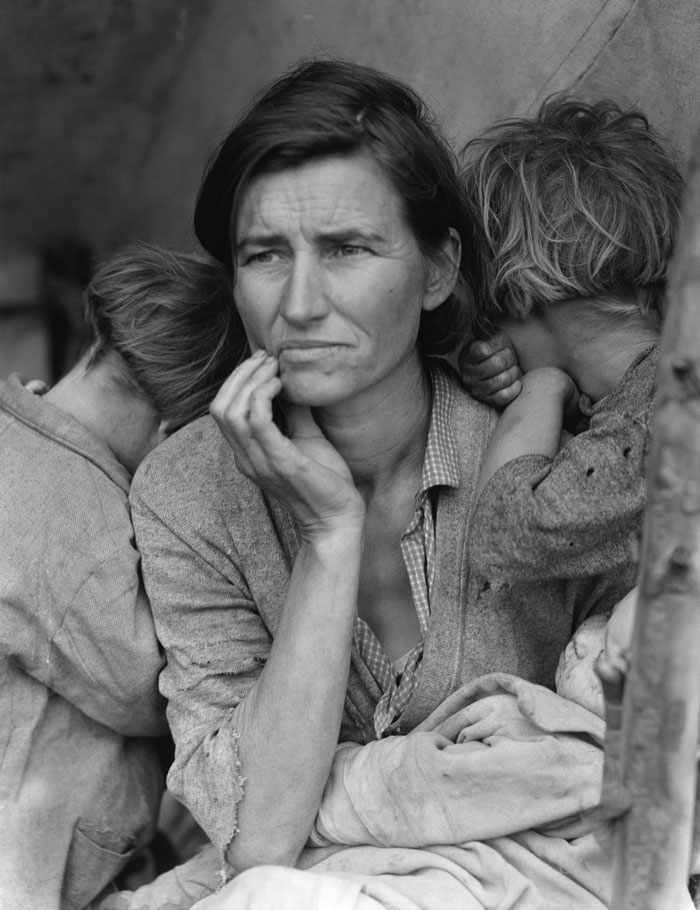

Anyone who has gazed at the faces in the Depression Era portraits by photographers Dorthea Lange and Walker Evans knows the powerful aesthetic effect of weathering. We see depth, meaning, hardship, and hope in these faces. Similarly the weathered face of a building tells a story. It tells us something about the place where they’re located: which way the wind blows, how the sun travels across the sky, and the intensity of a region’s climate. Weathering roots us in our sense of place, and in the passage of time. Over time each material will weather at a different rate, and in doing so provides us with contrasts between timelessness and ephemerality.

This year, I’ll be celebrating my 49th anniversary of circling around the sun, and with that daunting news, I have spent some time considering the wrinkles around my face and the grey hairs on my head. In life as in architecture, time is a component that can be honored or fought. Perhaps there is a grace to be found in accepting the effects of time, and wisdom to be discovered in the story told by a weathered face.